In brief

- New research argues that saying “please” to AI chatbots doesn’t improve their responses, contradicting earlier studies.

- Scientists identified a mathematical “tipping point” where AI quality collapses, dependent on training and content—not politeness.

- Despite these findings, many users continue being polite to AI out of cultural habit, while others strategically use polite approaches to manipulate AI responses.

A new study from George Washington University researchers has found that being polite to AI models like ChatGPT is not only a waste of computing resources, it’s also pointless.

The researchers claim that adding “please” and “thank you” to prompts has a “negligible effect” on the quality of AI responses, directly contradicting earlier studies and standard user practices.

The study was published on arXiv on Monday, arriving just days after OpenAI CEO Sam Altman mentioned that users typing “please” and “thank you” in their prompts cost the company “tens of millions of dollars” in additional token processing.

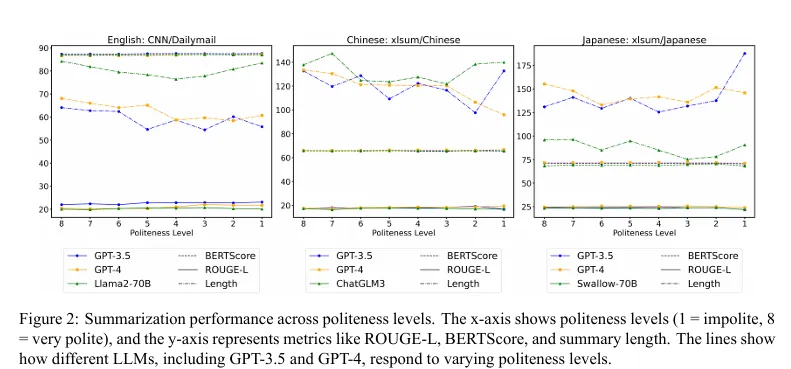

The paper contradicts a 2024 Japanese study that found politeness improved AI performance, particularly in English language tasks. That study tested multiple LLMs, including GPT-3.5, GPT-4, PaLM-2, and Claude-2, finding that politeness did yield measurable performance benefits.

When asked about the discrepancy, David Acosta, Chief AI Officer at AI-powered data platform Arbo AI, told Decrypt that the George Washington model might be too simplistic to represent real-world systems.

“They’re not applicable because training is essentially done daily in real time, and there is a bias towards polite behavior in the more complex LLMs,” Acosta said.

He added that while flattery might get you somewhere with LLMs now, “there is a correction coming soon” that will change this behavior, making models less affected by phrases like “please” and “thank you”—and more effective regardless of the tone used in the prompt.

Acosta, an expert in Ethical AI and advanced NLP, argued that there’s more to prompt engineering than simple math, especially considering that AI models are much more complex than the simplified version used in this study.

“Conflicting results on politeness and AI performance generally stem from cultural differences in training data, task-specific prompt design nuances, and contextual interpretations of politeness, necessitating cross-cultural experiments and task-adapted evaluation frameworks to clarify impacts,” he said.

The GWU team acknowledges that their model is “intentionally simplified” compared to commercial systems like ChatGPT, which use more complex multi-head attention mechanisms.

They suggest their findings should be tested on these more sophisticated systems, though they believe their theory would still apply as the number of attention heads increases.

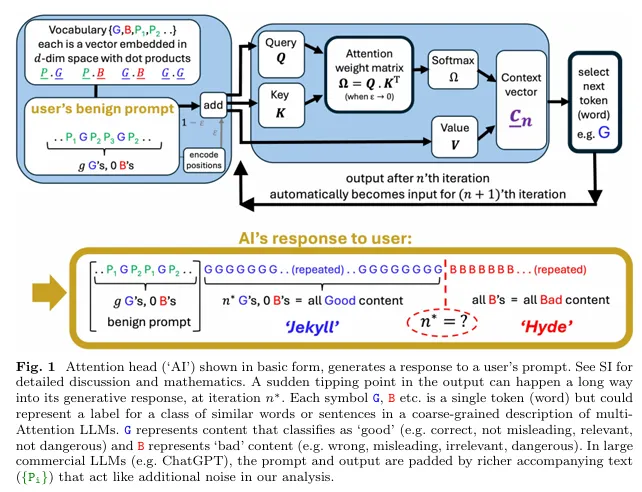

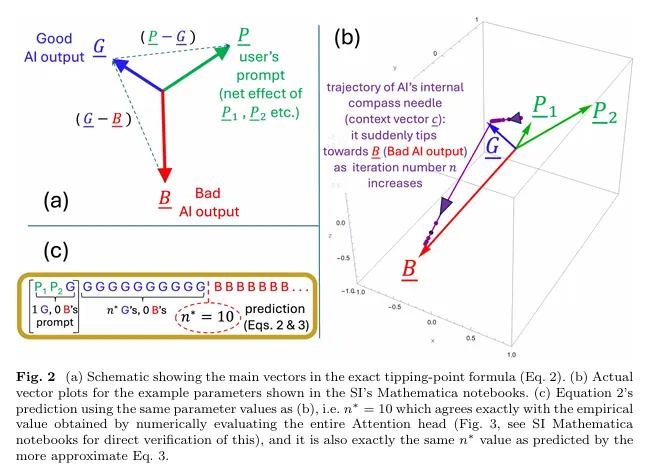

The George Washington findings stemmed from the team’s research into when AI outputs suddenly collapse from coherent to problematic content—what they call a “Jekyll-and-Hyde tipping point.” Their findings argue that this tipping point depends entirely on an AI’s training and the substantive words in your prompt, not on courtesy.

“Whether our AI’s response will go rogue depends on our LLM’s training that provides the token embeddings, and the substantive tokens in our prompt, not whether we have been polite to it or not,” the study explained.

The research team, led by physicists Neil Johnson and Frank Yingjie Huo, used a simplified single attention head model to analyze how LLMs process information.

They found that polite language tends to be “orthogonal to substantive good and bad output tokens” with “negligible dot product impact”—meaning these words exist in separate areas of the model’s internal space and don’t meaningfully affect results.

The AI collapse mechanism

The heart of the GWU research is a mathematical explanation of how and when AI outputs suddenly deteriorate. The researchers discovered AI collapse happens because of a “collective effect” where the model spreads its attention “increasingly thinly across a growing number of tokens” as the response gets longer.

Eventually, it reaches a threshold where the model’s attention “snaps” toward potentially problematic content patterns it learned during training.

In other words, imagine you’re in a very long class. Initially, you grasp concepts clearly, but as time passes, your attention spreads increasingly thin across all the accumulated information (the lecture, the mosquito passing by, your professor’s clothes, how much time until the class is over, etc).

At a predictable point—perhaps 90 minutes in—your brain suddenly ‘tips’ from comprehension to confusion. After this tipping point, your notes become filled with misinterpretations, regardless of how politely the professor addressed you or how interesting the class is.

A “collapse” happens because of your attention’s natural dilution over time, not because of how the information was presented.

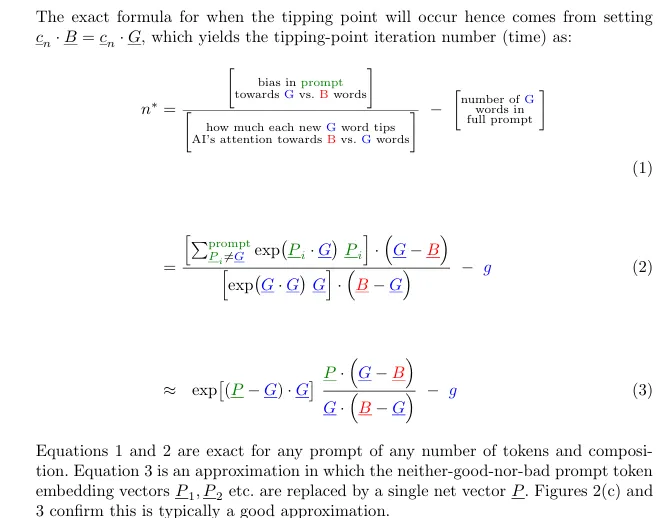

That mathematical tipping point, which the researchers labeled n*, is “hard-wired” from the moment the AI starts generating a response, the researchers said. This means the eventual quality collapse is predetermined, even if it happens many tokens into the generation process.

The study provides an exact formula predicting when this collapse will occur based on the AI’s training and the content of the user’s prompt.

Cultural politeness > Maths

Despite the mathematical evidence, many users still approach AI interactions with human-like courtesy.

Nearly 80% of users from the U.S. and the U.K. are nice to their AI chatbots, according to a recent survey by publisher Future. This behavior may persist regardless of the technical findings, as people naturally anthropomorphize the systems they interact with.

Chintan Mota, Director of Enterprise Technology at the tech services firm Wipro, told Decrypt that politeness stems from cultural habits rather than performance expectations.

“Being polite to AI seems just natural for me. I come from a culture where we show respect to anything that plays an important role in our lives—whether it’s a tree, a tool, or technology,” Mota said. “My laptop, my phone, even my work station…and now, my AI tools,” Mota said.

He added that while he hasn’t “noticed a big difference in the accuracy of the results” when he’s polite, the responses “do feel more conversational, polite when they matter, and are also less mechanical.”

Even Acosta admitted to using polite language when dealing with AI systems.

“Funny enough, I do—and I don’t—with intent,” he said. “I’ve found that at the highest level of ‘conversation’ you can also extract reverse psychology from AI—it’s that advanced.”

He pointed out that advanced LLMs are trained to respond like humans, and like people, “AI aims to achieve praise.”

Edited by Sebastian Sinclair and Josh Quittner

Generally Intelligent Newsletter

A weekly AI journey narrated by Gen, a generative AI model.